Atomic Bomb Casino

Atomic Liquors 917 Fremont Street Las Vegas, NV, 89101 702-982-3000 Email: info@atomic.vegas. Facebook: /atomiclasvegas Twitter: @atomicdtlv Instagram: @atomicliquors. Atomic Blonde (2017) Soundtrack 28 Jul 2017. Lorraine meets with Bremovych at a hotel room in Paris. Under Pressure. Queen.

One of the great vestiges of the Cold War is the Greenbrier bunker, a facility built to house all 535 members of Congress in the event of a nuclear attack.

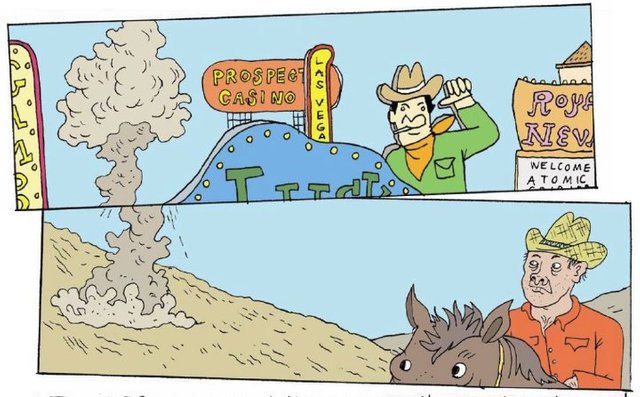

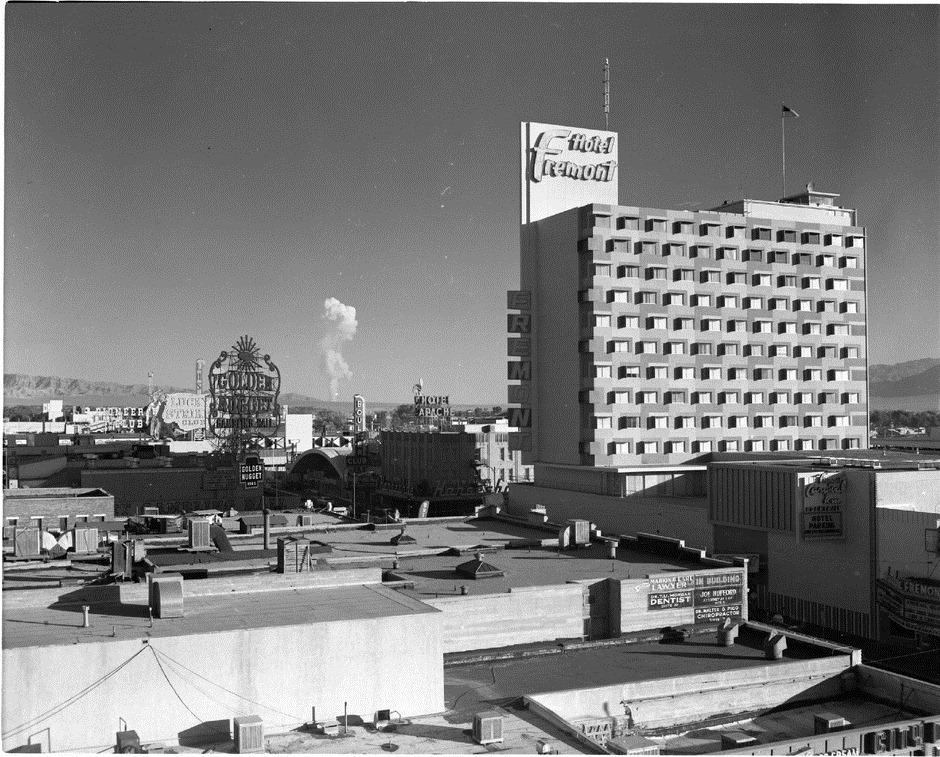

- And with the bombs being dropped once every three weeks, Las Vegas became known unofficially as “Atomic City,” a tourist destination with its very own nuclear fireworks show. People came from all over America to see the spectacle and Vegas’s population more than doubled.

- Kulka could only look on in horror as the bomb dropped to the floor, pushed open the bomb bay doors, and fell 15,000 feet toward rural South Carolina. Florence Museum Fortunately for the entire East Coast, the bomb's fission core was stored in a separate part of the plane, meaning that it wasn't technically armed.

- By the end of the decade the mushroom cloud symbol was used on billboards, casino marquees, advertisements, and even the cover of the Las Vegas High School yearbook. In the 1970s, the population doubled again, prompting casino owner Benny Binion to declare, “The best thing to happen to Vegas was the Atomic Bomb.”.

Construction

In 1955, Dwight D. Eisenhower instructed the Department of Defense to draft emergency plans for Congress in case of a nuclear strike. Even if Washington, DC was destroyed, American officials needed a procedure to maintain the continuity of government. As part of these efforts, the Army Corps of Engineers was charged with scouting the location of a nuclear bunker for the members of Congress. They ultimately selected the Greenbrier, a luxury resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

Greenbrier was chosen because of its location—relatively close and accessible to Washington, but far enough away to be safe from an atomic bomb—and because of its prior relationship with the United States government. During World War II, Greenbrier had served as an internment facility for Japanese, Italian, and German diplomats and then as a military hospital, where Eisenhower himself was at one time a patient. Although it returned to its original function as a hotel after the war, government officials occasionally held conferences at Greenbrier.

Construction on the bunker began in 1957. Government officials tried to hide the secret project by announcing the construction of Greenbrier’s “West Virginia Wing.” Construction workers and locals were suspicious, however, particularly about the sheer volume of concrete that was poured for the project. As construction worker Randy Wickline recalled, “Nobody came out and said it was a bomb shelter, but…they weren’t building it to keep the rain off them. I mean a fool would have known.” Truman Wright, the manager of the Greenbrier resort from 1951-1974, likewise remembered a contractor asking, “This is an exhibit hall? We’ve got 110 urinals we just installed. What in the hell are you going to exhibit?”

The $14 million project was completed on October 16, 1962, just before the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Originally codenamed Project X, the bunker was also known as Project Caspar and, during the 1980s, as Project Greek Island.

Inside the Bunker

The Greenbrier bunker is buried 720 feet underground. It would not survive a direct nuclear strike, but is capable of weathering a blast 15-30 miles away and protecting its occupants from fallout. The two-level facility is 112,544 square feet, roughly the size of two football fields on top of one another.

The bunker has four doors, all made by the Ohio-based Mosler Safe Company and shipped to Greenbrier by railway. The two largest, known as GH 1 and GH 3 and weighing 28 and 20 tons respectively, require 50 pounds of force to open. Once sealed, the bunker would have had enough air to last 72 hours, after which a ventilation system would filter air from the outside.

Although most of the bunker was a closely guarded secret, its largest halls—intended for sessions of Congress—were actually part of the Greenbrier hotel and would have been sealed off only in the event of an attack. The largest, Exhibit Hall, was designed to host joint sessions of Congress. A Greenbrier brochure from the 1960s advertised the hall to guests: “The floor is finished with a beautiful plastic terrazzo designed to support unlimited weight.” Just off of Exhibit Hall are two smaller auditoriums: the 440-seat Governor’s Hall, intended for the House of Representatives, and the 130-seat Mountaineer Room, which would have hosted members of the Senate.

A hidden passage, marked by a door which reads, “Danger: High Voltage Keep Out,” leads to the rest of the bunker. In the event of an attack, congressmen would have first been ushered to the decontamination room, where they would have stripped, showered, and put on uncontaminated clothes. The dormitories consist of 18 rooms, each built to house 60 people in metal bunk beds. There is also a kitchen and a 400-seat cafeteria, which was at one point decorated with fake windows featuring scenic views. The upper level contains storage space and offices for congressional leaders.

Among other interesting features, the bunker’s power room includes a “pathological waste incinerator” designed to cremate bodies. The Congressional Record Room, in addition to holding files, houses the only weapons in the facility: a relatively modest collection of rifles, pistols, nightsticks, and helmets—essentially riot gear. The bunker also has a hospital, operating room, and pharmacy, which once kept a plentiful supply of antidepressants. According to journalist Paul Lieberman, the bunker maintained “a tiny jail with two boxes of straitjackets” just in case “congressmen went bonkers.”

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the bunker is the vast television, radio, and communications facilities. In the event of an attack, congressmen would have been expected to give speeches broadcast to whatever was left of the American population. The TV conference room even includes a backdrop of the Capital Building, giving the illusion of normalcy.

Preparing for Doomsday

After its construction, the Greenbrier bunker was maintained by 12-15 permanent government employees who worked undercover as members of an Arlington-based television repair company called Forsythe Associates. According to Paul Fritz Bugas, the former superintendent of the bunker, the government workers at Greenbrier spent about 20% of their time doing TV work for the hotel, with the remainder devoted to bunker maintenance.

Among other supplies, the bunker was provided with enough food for 1,000 people to last 60 days. Government employees also had to constantly update their plans based on who the current members of Congress were. “For 30 years, every one of these 1,100 beds was assigned to somebody,” explained Greenbrier historian Bob Conte. “For that 30 years you had to make sure all the filters were changed, all the pharmaceuticals were up-to-date, and all the food was ready to go.”

The actual procedure for bringing congressmen to the bunker remains somewhat unclear. Greenbrier is a five hour drive or a one hour flight (the local airport was expanded in 1962) from Washington, so it would have required advance warning of an attack to bring all 535 members of Congress. Almost no members were aware that the bunker existed––only the leadership was ever briefed. Former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill recalled, “I never mentioned [the evacuation plan] to anybody. But every time I went down to the Greenbrier I always used to look at the hill and say, ‘Well that’s where we’re supposed to live in the event something happens, and that’s where we’re going to do business, maybe under the tennis courts.’”

There remains some ambiguity on whether congressmen would have been allowed to bring their families to the bunker. O’Neill recalled being told that he could not bring his family, commenting, “I kind of lost interest in it when they told me my wife would not be going with me.” Paul Fritz Bugas, however, maintained that there were plans to expand bunker facilities in order to accommodate families, although it is unclear if or when this project ever occurred.

The Greenbrier Bunker Today

The bunker remained a closely guarded secret until 1992, when Washington Post reporter Ted Gup revealed its existence in his article, “The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway.” Given that its secure location was one of the primary guarantees for its defense, the bunker was quickly decommissioned. Bugas was critical of the article, explaining, “We felt a disservice had been done. I’m not talking to us personally, but to our country’s security.” Gup, however, argued that by 1992 the bunker was essentially obsolete: “The bunker was built when bombers took hours to go over the polar ice caps. The warning time was many hours. We're now talking minutes, if not less.”

In 1995, the Greenbrier resort began offering tours of the bunker to its guests. In 2006, the tours were expanded to the general public. Tours are still offered today, but no cameras are allowed inside the bunker.

Atomic Bomb Church

There is speculation that the U.S. government has built a new bunker for Congress since the existence of the Greenbrier bunker was revealed in 1992. If there is such a bunker, very few people know about it. As Bill Arkin of the Washington Post commented, “If you’re a normal member of Congress, my guess is that you know nothing. You really know nothing.”

The Bunker At The Greenbrier

Atomic Bomb China

“Virtual Shelter Tours: Congressional Relocation Bunker, Greenbrier Resort, West Virginia.” Civil Defense Museum. http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/greenbriar/index.html